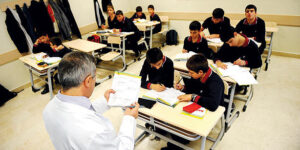

Turkey isgoing to apply the education reform passed by the government in March in the approaching school year, but educators and parents think that the Ministry of Education hasn’t taken adequate measurements to lay the essential groundwork for a smooth transition.

The reform, referred to as 4+4+4 — 4 years of primary, middle and high school — lowers the school beginning age to 60 months plus, from a previous 72 months plus. This is anticipated to stimulate a score of troubles, as the number of children beginning school this year might be double the figure in a normal year. Educators’ unions and parents have highlighted the deficiency of facilities to accommodate the surge in students.

The education reform of the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) has demonstrated controversial. Critics debate that the government is trying to de-secularize Turkey’s education system by letting imam-hatip schools, with their religious course of study, to open middle schools. Previously, Turkish children would have 8 years of primary education abided by high school. The government tells it’s applying the traditional and universally accepted standard of three schools before university. Critics accuse the government of acting out of revenge against the Feb. 28, 1997 military intercession, which saw the closing down of imam-hatip middle schools. Indeed, some schools have complained of being turned into imam-hatip schools against the will of teachers and parents.

The principal of an İstanbul school, who asked not to be named as public officials are not authoritative to talk to the press, told that in a normal school year they’ve enrollments of 220 first graders (30 to 35 students per classroom). “Til now we have 350 affirmed students,” he told, which brings the number of students in the school, which has seven first-year classes, to 50 students. “All the same, that’s not all,” he noted. As the new system allows the optional enrollment of children between 60 and 66 months based on parental permission, 150 applications are pending. “We told families that their children are too young, that they shouldn’t rush, but nobody has changed their mind so far.”

The school is in Esenyurt, a poor zone in İstanbul that is home to a large number of slum settlements, a place where, for most families, sending a child to school is an easy way of holding him or her off the streets. Accordingly, such families are more probable to take the choice of sending their children to school younger.

Indeed, if none of the parents in Esenyurt with children whose ages fall within the optional category for schooling decide to keep their children at home, there might be as many as seventy kids in one classroom. “We’re in a really difficult position. They’ll have to sit 3 or 4 kids in one row,” the principal told. “These children will be the guinea pig generation. Their hand muscles aren’t even developed enough to write. The curriculum is also not very clear yet. What are we supposed to do with these children? Are we going to read them story books?”

There have been reports pointing that in some schools, schoolrooms might contain as many as 80 students.

The Union of Education and Science Laborers (Eğitim Sen) recently brought out a affirmation listing troubles which are probably to rise from the reform. The union noted that first-time enrollments will increase by 75 percent this year, but that no new schoolrooms have been constructed; the first problem to be fronted by schools such as that in Esenyurt.

Afrikaans

Afrikaans Shqip

Shqip አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية Հայերեն

Հայերեն Azərbaycan dili

Azərbaycan dili Euskara

Euskara Беларуская мова

Беларуская мова বাংলা

বাংলা Bosanski

Bosanski Български

Български Català

Català Cebuano

Cebuano Chichewa

Chichewa 简体中文

简体中文 繁體中文

繁體中文 Corsu

Corsu Hrvatski

Hrvatski Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Nederlands

Nederlands English

English Esperanto

Esperanto Eesti

Eesti Filipino

Filipino Suomi

Suomi Français

Français Frysk

Frysk Galego

Galego ქართული

ქართული Deutsch

Deutsch Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά ગુજરાતી

ગુજરાતી Kreyol ayisyen

Kreyol ayisyen Harshen Hausa

Harshen Hausa Ōlelo Hawaiʻi

Ōlelo Hawaiʻi עִבְרִית

עִבְרִית हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hmong

Hmong Magyar

Magyar Íslenska

Íslenska Igbo

Igbo Bahasa Indonesia

Bahasa Indonesia Gaeilge

Gaeilge Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Basa Jawa

Basa Jawa ಕನ್ನಡ

ಕನ್ನಡ Қазақ тілі

Қазақ тілі ភាសាខ្មែរ

ភាសាខ្មែរ 한국어

한국어 كوردی

كوردی Кыргызча

Кыргызча ພາສາລາວ

ພາສາລາວ Latin

Latin Latviešu valoda

Latviešu valoda Lietuvių kalba

Lietuvių kalba Lëtzebuergesch

Lëtzebuergesch Македонски јазик

Македонски јазик Malagasy

Malagasy Bahasa Melayu

Bahasa Melayu മലയാളം

മലയാളം Maltese

Maltese Te Reo Māori

Te Reo Māori मराठी

मराठी Монгол

Монгол ဗမာစာ

ဗမာစာ नेपाली

नेपाली Norsk bokmål

Norsk bokmål پښتو

پښتو فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português ਪੰਜਾਬੀ

ਪੰਜਾਬੀ Română

Română Русский

Русский Samoan

Samoan Gàidhlig

Gàidhlig Српски језик

Српски језик Sesotho

Sesotho Shona

Shona سنڌي

سنڌي සිංහල

සිංහල Slovenčina

Slovenčina Slovenščina

Slovenščina Afsoomaali

Afsoomaali Español

Español Basa Sunda

Basa Sunda Kiswahili

Kiswahili Svenska

Svenska Тоҷикӣ

Тоҷикӣ தமிழ்

தமிழ் తెలుగు

తెలుగు ไทย

ไทย Українська

Українська اردو

اردو O‘zbekcha

O‘zbekcha Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt Cymraeg

Cymraeg isiXhosa

isiXhosa יידיש

יידיש Yorùbá

Yorùbá Zulu

Zulu