Israel’s population registry lists a slew of “nationalities” and ethnicities, among them Jew, Arab, Druse and more. But one word is conspicuously absent from the list: Israeli.

Residents cannot identify themselves as Israelis in the national registry because the move could have far-reaching consequences for the country’s Jewish character, the Israeli Supreme Court wrote in documents obtained Thursday.

Residents cannot identify themselves as Israelis in the national registry because the move could have far-reaching consequences for the country’s Jewish character, the Israeli Supreme Court wrote in documents obtained Thursday.

The ruling was a response to a demand by 21 Israelis, most of whom are officially registered as Jews, that the court decide whether they can be listed as Israeli in the registry. The group had argued that without a secular Israeli identity, Israeli policies will favor Jews and discriminate against minorities.

In its 26-page ruling, the court explained that doing so would have “weighty implications” on the state of Israel and could pose a danger to Israel’s founding principle: to be a Jewish state for the Jewish people.

The decision touches on a central debate in Israel, which considers itself both Jewish and democratic yet has struggled to balance both. The country has not officially recognized an Israeli nationality.

National and ethnic loyalties are often layered in Israel, a country founded on the heels of the British colonial mandate and initially populated by Jewish immigrants along with a small indigenous Jewish population and a larger Arab community.

There are Jews and Arabs. But the Jewish majority distinguishes itself between those from eastern Europe and those whose families originated in Arab countries. These communities are further divided based on the country, or even the village, their ancestors came from.

The 20 percent Arab minority also has Israeli citizenship, and many identify themselves as either Christian or Muslim. Israel is also home to a smattering of other minorities.

The national population registry lists a person’s religion and nationality or ethnicity, among other details. Any Jew, no matter what his country of origin, is listed as a Jew. Arabs are marked as such and other minorities, such as Druse, are listed by their ethnicity.

Judaism plays a central role in Israel. Religious holidays are also national holidays, and religious authorities oversee many ceremonies, such as weddings and funerals. Yet since Israel’s establishment in 1948, a distinct Israeli nationality has emerged, including foods, music and culture, and for most Jews, compulsory military service. While roughly half of Israel’s Jewish population define themselves first and foremost as Jewish, 41 percent of Israelis identify themselves as Israeli, according to the Israel Democracy Institute, a think-tank.

In the Supreme Court case, the 21 petitioners argued that Israel is not democratic because it is Jewish. They say that the country’s Arab minority faces discrimination because certain policies favor Jews and that a shared Israeli nationality could bring an end to such prejudice and unite all of Israel’s citizens.

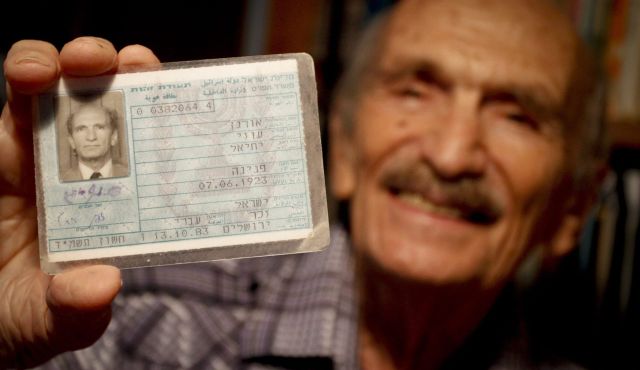

“The Jewish identity is anti-democratic,” said Uzzi Ornan, the main petitioner who runs “I am Israeli,” a small organization devoted to having the Israeli nationality officially recognized.

“With an Israeli identity, we can be secure in our democracy, secure in equality between all citizens,” said Ornan, a 90-year-old professor of computational linguistics at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa.

Israeli Arabs have long contended that, despite their citizenship, they are victims of official discrimination, with their communities receiving fewer resources than Jewish towns. While some Arabs have made strides in recent years in entering the Israeli mainstream, they are on average poorer and less educated than their Jewish counterparts.

The court’s deliberation focused mainly on how an officially recognized Israeli identity could pose a threat to Israel’s founding ideals and cause disunity. The court said it was not casting doubt on the existence of an Israeli nation.

Anita Shapira, a professor emeritus of Jewish history at Tel Aviv University, said that Judaism and Jewish nationalism go hand in hand and that if nationalism develops into an Israeli one, the Jewish essence will be lost. She also said it could estrange Jews from other countries whose connection to Israel is through religion.

“The attempt to claim that there is a Jewish nationality in the state of Israel that is separate from the Jewish religion is something very revolutionary,” she said.

Ornan also appealed to Israel’s interior minister in 2000 and took the matter to court in 2003 in a failed attempt to identify as Israeli. He vowed to continue his campaign.

Others have also tried to tackle the population registry. The late Israeli author Yoram Kaniuk persuaded a court in 2011 to have him listed as being “without religion,” though his ethnicity remained “Jewish.” Secularists considered the change a coup.

HDN