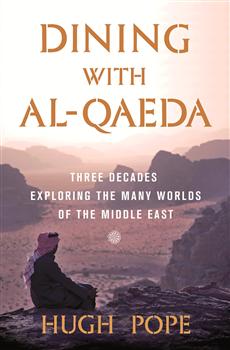

‘Dining with al-Qaeda: Three Decades Exploring the Many Worlds of the Middle East’ by Hugh Pope (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2010, $27, 332 pages)

Hugh Pope is perhaps slightly unfortunate to have written “Dining with al-Qaeda” just before the Arab revolts erupted across the Middle East. As it is, you read his reflections on 30 years of reporting in the region with the knowledge of what was to come always lurking in the back of your mind. I wonder what he makes of today’s events in the Arab world; he comes across as a natural optimist, but three decades of covering the region have disabused him of any fantasies dreamt up in the Oriental Studies department at Oxford. Still, he’s able to stay free of any of the hard-boiled cynicism that affects many others in his line of work, and has written a brilliant, vivid book that is full of wit and intelligence.

One result of Pope’s many years of experience is a refusal to succumb to overarching intellectual schema, which he says is born of a “long-lasting suspicion of all ideological interpretations of the Middle East.” Instead, he allows himself “to go with the flow of the truer and more interesting confusion of everyday life … the vivacious human contact that make the region so addictive.” Far from making the book a lightweight read, this ideological skepticism has been hard-won through years of reporting some of the most intractable conflicts in the region. He may be buccaneering, but Pope has no spectacular Anthony Loyd-style reporter’s tale of psychological breakdown and heroin addiction, substituted by thrills on the perilous front line. Instead, he simply writes fluently of what he has observed and learnt, with a nice line in pithy summaries of people and places. OfIran he writes: “I despaired of my own side for giving so many winning arguments to someone as sanctimonious and hypocritical as Khameini.” Of the Yezidis: “high on the scale of oppression, even in the Middle East’s competitive arena.” Of Turkey: a “free but distorted burlesque of conflicting viewpoints.” Of Lebanon: “Israelis were all over the south, neck-deep in the Middle Eastern delusion that conquerors were keepers.” Of Saddam’s Iraq: “a sinister B-movie.”

Much of the book is spent reflecting on Pope’s frustrating experience as a Wall Street Journal correspondent in Iraq as the war drums started rolling after September 11, and during the subsequent occupation. A principled and thoughtful journalist, he’s excellent at describing his exasperation at his own apparent futility to “bridge fully the gap between Middle Eastern reality and American perceptions” during those dark days – a particularly tough task considering the state of the Journal’s tub-thumping opinion pages at the time. He doesn’t say it explicitly, but the disillusioning professional experience of the second Iraq War probably did as much as his family commitments to finally convince him to throw in the towel after 30 years on the beat. “As someone who tried to write articles that challenged the logic of that invasion, I felt by turns futility, emasculation, depression, and even physically sick,” he writes at one point.

The title “Dining with al-Qaeda” is grabby – (though somewhat less so than fellowreporter Edward Behr’s “Anyone Here Been Raped and Speaks English?”) – and refers to Pope’s nail-biting encounter with an al-Qaeda operative in Saudi Arabia shortly after 9/11. On the whole, however, he has too much experience to suggest that the region can be reduced to such sensational episodes. While it’s highly entertaining, “Dining with al-Qaeda” is also an astute warning from an authoritative voice about the clichés and blind spots that distort coverage of the Middle East.

HDN