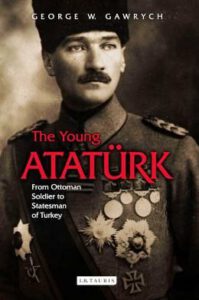

‘The Young Atatürk: From Ottoman Soldier to Statesman of Turkey’ by George W. Gawrych (I.B. Tauris, 2013, $35, 288 pages)

There has been a resurgence of popular interest in Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of late. Almost all opposition groups have been selectively reconsidering the legacy of the Turkish Republic’s founder, in response to the country’s bitter recent culture wars and in the afterglow of the summer’s Gezi protests. Abroad, interest inAtatürk was also piqued by anti-government protesters photographed waving around his picture, so it’s probably an auspicious time to be publishing a new book on the man. This title by historian George W. Gawrych is primarily focused on the military aspect of the “young Atatürk,” and self-admittedly doesn’t aim to provide a complete assessment of its subject’s broader legacy. Still, it does leave the reader wishing for a rather more comprehensive appraisal; the youngAtatürk may be inextricable from the military Atatürk, but considering either with only minimal reference to the broader sweep of Ottoman decline and republican revival makes for a pretty dry read.

There has been a resurgence of popular interest in Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of late. Almost all opposition groups have been selectively reconsidering the legacy of the Turkish Republic’s founder, in response to the country’s bitter recent culture wars and in the afterglow of the summer’s Gezi protests. Abroad, interest inAtatürk was also piqued by anti-government protesters photographed waving around his picture, so it’s probably an auspicious time to be publishing a new book on the man. This title by historian George W. Gawrych is primarily focused on the military aspect of the “young Atatürk,” and self-admittedly doesn’t aim to provide a complete assessment of its subject’s broader legacy. Still, it does leave the reader wishing for a rather more comprehensive appraisal; the youngAtatürk may be inextricable from the military Atatürk, but considering either with only minimal reference to the broader sweep of Ottoman decline and republican revival makes for a pretty dry read.

The book opens with an account of Mustafa Kemal’s early years studying at the Ottoman military high school in Salonica, his hometown. After graduating, he became involved with the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the group of “Young Turk” officers that overthrew Sultan Abdülhamid II in 1908. Mustafa Kemal had the good fortune of not yet being high enough in the Young Turk echelons to be tarred by the mess that followed the CUP’s seizing of power, when the empire limped from crisis to crisis. However, during the Great War he commanded the heroic but tragic defence of Gallipoli in 1915, emerging with a strong reputation from a brutal slugfest that ended with around 500,000 dead on all sides. The eventual armistice later imposed by the victorious Entente powers was a peace without honour, demanding the total and unconditional surrender of the Ottoman forces. The terms amounted to the complete dismemberment of almost all of the empire’s remaining territory, with the spoils divided between the British, the French, the Italians, the Greeks, and the Armenians. However, with the CUP leadership either discredited or on trial, and the sultan’s imperial retinue effectively held hostage in occupied Istanbul, the seeds of an independence struggle were already being sown by patriotic military figures in Anatolia, to which Mustafa Kemal quietly departed.

Unfortunately, it’s around this crucial point that the book becomes a trudge, with Gawrych providing exhaustive (and exhausting) blow-by-blow accounts of every major military clash that took place between the Turks and the Greeks. Of course, a military historian cannot really be criticised for focusing on this aspect of things, but such intricate accounts of the minutiae of military strategy will probably be trying for even the most enthusiastic reader. Wading through them sometimes feels as attritional as the campaigns being described. Still, some relief does come; Gawrych gives a revelatory account of the often overlooked revolts against the nationalists that were staged throughout the independence struggle by militia groups across Anatolia, (not just in Kurdistan). Particularly striking is the book’s description of the brutal crushing of a localGreek rebellion in the western Black Sea region, in which tens of thousands were killed and deported.

Clausewitz wrote that the “statesman is inseparable from the soldier,” and this was certainly the case with Atatürk. Gawyrch’s book is subtitled “From Soldier to Statesman,” but in fact the statesman never really emerged independent from the soldier in Mustafa Kemal; the rigid, positivistic outlook that he acquired as a soldier deeply informed his later actions as president. Nevertheless, the book is also keen to make clear that this rigidity never overshadowed the robust pragmatism that marked his political steps throughout the independence struggle. Although fixed in his plans to establish a secular state defined by a restrictive “Turkism,” the young Mustafa Kemal was never shy in playing the broader Islamic card when seeking to rally popular support behind his forces. Pragmatism also defined relations with the Soviet Union, which he solicited for crucial financial and military assistance – Gawrych mentions a remarkable private letter sent by Mustafa Kemal to Lenin in 1922, in which he expressed the need to found a bloc to resist the methods of “imperialism and capitalism.”

The book ends with the declaration of the republic in 1923, before the most controversial episodes of Mustafa Kemal’s rule, and also before the major revolutionary secularising reforms that he would later enforce. However, almost inadvertently, its account of the near “total war” that Turkey went through for close to two decades gives an idea of the conditions that allowed those reforms to be pushed through. Faced with a brutalised population exhausted by war on a purged Anatolian landscape, and emboldened by the political capital that came with defeating the Greeks, Mustafa Kemal had unique conditions in which to push through his attempted root and branch social revolution. Frustratingly, exploring the wider significance of this process lies outside the scope of Gawrych’s book.

HDN