Why did the bodies of 110 men suddenly wash up in the river running through Aleppo city six weeks ago? A Guardian investigation found out.

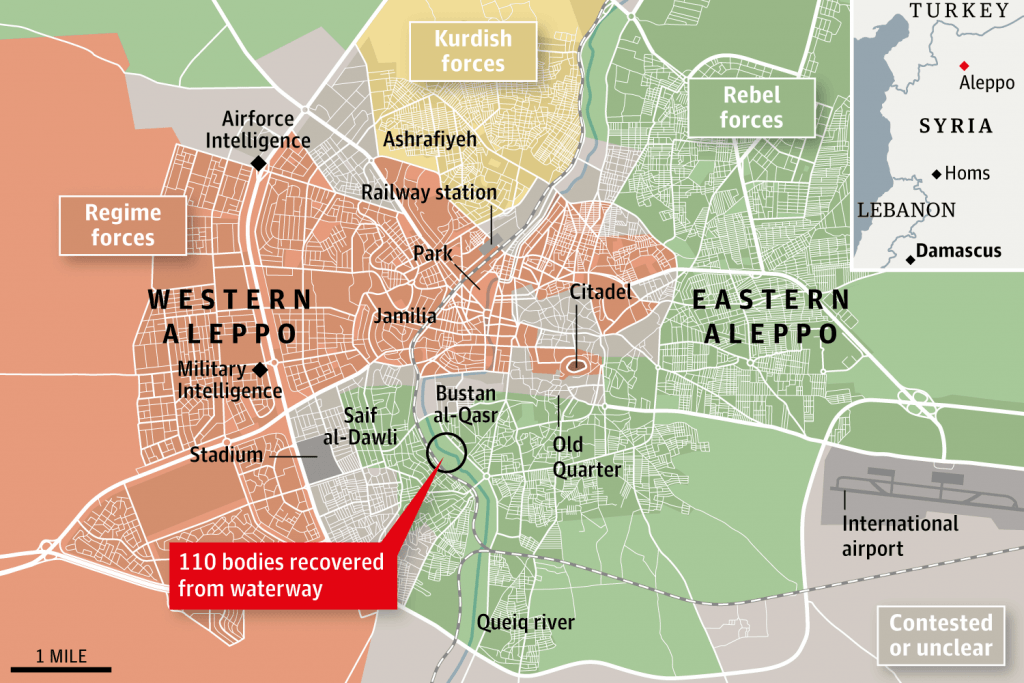

It is already one of the defining images of the Syrian civil war: a line of bodies at neatly spaced intervals lying on a river bed in the heart of Syria’s second city Aleppo. All 110 victims have been shot in the head, their hands bound with plastic ties behind their back. Their brutal execution only became apparent when the winter high waters of the Queiq river, which courses through the no man’s land between the opposition-held east of the city and the regime-held west, subsided in January.

It is already one of the defining images of the Syrian civil war: a line of bodies at neatly spaced intervals lying on a river bed in the heart of Syria’s second city Aleppo. All 110 victims have been shot in the head, their hands bound with plastic ties behind their back. Their brutal execution only became apparent when the winter high waters of the Queiq river, which courses through the no man’s land between the opposition-held east of the city and the regime-held west, subsided in January.

It’s a picture that begs so many questions: who were these men? How did they die. Why? What does their story tell us about the wretched disintegration of Syria? A Guardian investigation has established a grisly narrative behind the worst – and most visible – massacre to have taken place here. All the men were from neighbourhoods in the eastern rebel-held part of Aleppo. Most were men of working age. Many disappeared at regime checkpoints. They may not be the last to be found. Locals have since dropped a grate from a bridge, directly over an eddy in the river. Corpses were still arriving 10 days after the original discovery on January 29, washed downstream by currents flushed by winter rains.

Just after dawn on 29 January, a car pulled up outside a school being used as a rebel base in the Aleppo suburb of Bustan al-Qasr with news of the massacre. Since then a painstaking task to identify the victims and establish how they died has been inching forwards. The victims, many without names, were mostly buried within three days — 48 hours longer than social custom dictates, to allow for their families to claim them.

Ever since, relatives have been arriving to identify the dead from photographs taken by the rescuers. Each family member who has made the journey to a makeshift office, set up inside a childcare centre, brings with them accounts of when they last saw their father, son, cousin, or brother and where he had travelled before he was murdered.

There are no women on the grisly slideshow of dead men that is replayed in melancholy slow motion every time a relative arrives. Nor are there more than a handful of males aged over 30. Most of the dead dragged from Aleppo’s Queiq River were men of working age.

Another thread strongly unites the fate of the river massacre victims; each of them had either been in the west of the city, or had been trying to get there. They had to pass though checkpoints run by the Syrian army, or their proxy militia, the Shabiha. The process involved handing over identification papers that detailed in which area of the city the holder of the papers lived.

In mid-February, the Guardian interviewed 11 family members of massacre victims in the Bustan al-Qasr area, who all confirmed that their dead relatives had vanished in regime areas, or had been trying to reach them. Two other men who had been arrested at regime checkpoints and later freed were also interviewed. Both alleged that mass killings had taken place in the security prisons in which they had been held. They identified the prisons as Air Force intelligence and Military Security — two of the most infamous state security facilities in Syria.

“If they took you to the park, you were finished,” said one of the men, who had been freed in mid-January. “We all knew that. It is a miracle that I am standing here talking to you.”

The man, in his early 20s, refused to be identified even back in the relative safety of the east of the city. Nowadays, he spends his mornings on the banks of the river, waiting for more bodies to float down.

The concrete ledge from where the bodies were recovered is now covered by waters which, on 29 January, had receded leaving the sodden remains exposed, blood oozing from single bullet wounds to each of their shattered skulls.

Further north, around four kilometres upstream is the park that the man speaks about, a large public space near the Queiq River in west Aleppo. The rebels in the east suspect that the bodies they recovered may have drifted from this point while waters were flowing strongly in the last week of January. Their suspsicions centre on two witnesses who came forward in the days following the massacre.

One of them, Abdel Rezzaq, 19, arrived at the Revolutionary Security office, run from the abandoned daycare centre, in a muddy narrow lane in the heart of Bustan al-Qasr. Together with his parents, he wrote a hand-written statement alleging that, while inside the Air Force intelligence prison, he had heard the sounds of 30 men being shot dead. We found Abdel Rezzaq, now working as a straight vendor selling coffee in Bustan al-Qasr.

“I was living in Bustan area (in the west) and I was working as a carpenter,” he said. “I went downtown (in west Aleppo) to buy a falafel sandwich. The military caught and they started beating me all over my body and they were saying that I am with the Free Syria Army. They beat me for 8 days day and night and demanded I confess. They were transferring me from one base to another airforce base.”

“I was arrested on the 10th of October and stayed (in prison) for about 2.5 months to 3 months.”

“Before I left the prison, they took 30 people from isolation cells and killed them.”

Abdel Rezzaq said he was being held in Block 4, within earshot of the solitary confinement cells and the area where he alleges the prisoners were taken, then executed. “They handcuffed them and blindfolded them and they were torturing them till they died.”

“They poured acid on them. The smell was very strong and we were suffocating from it. Then we heard gunshots. The next day they put me and some of the others in front of men with guns, but they didn’t shoot at us. They freed me later that day.”

“I heard women screaming. They were pouring alcohol on us and cursing us. Only God got us out of there, no-one gets out alive. And only god knows what happened to the rest of the people who were in there. I will fight for this cause because I want the whole world to see what is happening.”

The account of the man who refused to be identified matched Abdel Rezzaq, although he claimed he was held in the Military Security prison.

“I was there for a month,” he said. “Then one night they took us to an area outside, it was near a park and I thought that was it. I was preparing for death through by praying and they started shooting along a wall where they had libed people up. There were about four guys next to me, to my right, and they stopped shooting. I heard one officer say ‘let them go’. And here I am. I will stay waiting for these bodies for the rest of the war. I cannot believe I am here.”

As the scale of the massacre became clear, Mahmoud Rezk and the unit near the frontline that had first been alerted to what had happened, started to receive bereaved family members.

On 10 February, almost two weeks after the bodies were found, two brothers arrived at the centre to look for their father. Less than five minutes later, both stood sobbing tears of unfathomable grief in front of a wall mural of a red Teletubby. “My father was working in the national bank,” wept Mahmoud al-Drubi. He was married to three women. He was staying with one of his wives (in Ashrafiyeh in west Aleppo) and he told her that he is going to work and it has been 22 days since he disappeared. He was working in an unliberated area. The regime did this to him.”

In the same courtyard of incongruous frivolity, Sheikh al-Aurora sits in front of a Minnie Mouse mural and insists that his family will take revenge for the death of his cousin, Mohammed Hamandush. The Sheikh identified himself as a member of the Free Syria Army, but insisted Mohammed, 18, had not been.

“I am one of the resistance fighters in Aleppo,” he said. “I am fighting the terrorist regime. I used to work with Syrian state television and I left the regime two years ago.

“Mohammed was going to the dentist in Jamilia and he was taken by the military. He was arrested because he was young and the military thought he was with the FSA.

“We knew where he was being held and his father went to see him but the military told him that he will be joining the army now. Several days later, his body ended up in the river “This is a dictator’s regime. They took that kid to join the army and then they killed him. This is because he was a Sunni. This war is obvious. This is a message from the Shia regime to the Sunnis.

“The image of my cousin was horrifying. His face was wrapped with nylon bag and with a tape to make sure he will be dead not only from the bullet but from suffocating. It is heart breaking. Killing Bashar and all of the shabiha won’t be enough revenge.”

Another man, who identified himself as Abu Lutfi, also claimed that his family had tracked down their missing relative, Mohammed Waez to a military prison in West Aleppo “He was a merchant and he was stopped at the checkpoint and was taken.We went to ask about him and the military told us that he was with them and in 10 days he will be released. Instead, 10 days later, we found his body in the river. He was handcuffed and his legs were bound. He was shot in the head.

“I am covering my face because if the regime recognizes my face, I will be dead and every single member of my family will be dead. They will kill us and no one can find us. We are for sure with the revolution. We served the military for 40 years and now this is the army that is attacking and killing us.

“This is a message from the army; every time the FSA will step forward, we will kill more civilians. Now the families of each victim are going to join the FSA.”

Another man, Amer al-Ali, from Dar al-Izza, about two kilometres west of Bustan al-Qasr, and a member of the FSA, said his family is now also seeking revenge.

“I am working as a fighter in Katibat Majd al-Islam. Two of my cousins, Yassin, 20, and Omar, 14, were tailors. They went missing 5 days before the massacre. I knew the army had a checkpoint in their area and I told them to be careful. They were the main financial supporters to their families. They went to work (in the west) and I saw them on their way to work. It was getting late and their father came to me asking if I saw them and we were searching for them. Several days later, we heard about the massacre and we went to retrieve their bodies.

“Their mother asked if she can join the FSA to take revenge and so did their father. They only have two daughters left and now the whole family wants to join a jihad.”

Dealing with the dead in Aleppo has a medieavel feel. Bodies dragged from the river in the days and weeks after the massacre were laid on footpaths outside the school yard, a simple plastic sheet covering the grey, shrivelling skin. The few who remained in Bustan al-Qasr walk past heads down, no longer stopping to look as they go about life in a city at war.

Some families asked the rebel unit to bury them on their behalf. Such a plea is highly unusual in this war. Here, like in conflicts elsewhere in the world, the final act of burial is akin to closure for grieving families. But, the request illustrated the depth of Aleppo’s divide and the desperate decisions that some families are being forced to make in order to maintain their incomes in a city where most commerce has ground to a halt. Little works in Aleppo anymore. Electricity has been dwindling for months and is now nearly non-existent. Rubbish is piled in football-field sized festering heaps. Even the flow of running water, potable from the tap, has slowed to a trickle.

All the relatives who requested that the rebels bury their relatives’ remains, without them being present, still worked in the west of the city. Some also lived there. Others had to cross from the east through checkpoints on most days.

“One of the (victims) had a mobile shop and they spoke to his father and then took his son away,” said Rezk. The next day, the father came to the river bank and found his son’s body. He decided to bury his son (in the east) because he was worried of taking his son’s dead body to where he lives. He thought they would kill him.”

Rezk displayed a handwritten note, which was a aimple authorisation from another father to bury his sons in the east.

“He was still working in an unliberated area and he had three sons, two of whom were dead. He didn’t want to talk about it with us. He just signed the note and left and we put them in the martyr’s grave.”

The graveyard Rezk spoke about was a children’s playground. All semblance of fun in this muddy stretch of rusting green swings and slides had long ago been surrendered to the grim reality of dealing with death in a city that no longer functions. Only a corner of the playground — for now — has been commandeered by grave diggers, men who swing shovels over their naked torsoes in the bitter cold and a small digger that scrapes at the soil, ever so gently for such a strong machine.

In the days following the massacre, Syrian officials blamed ‘terrorist groups’ for the deaths. State television broadcast a ‘confession’ from an alleged member of Jabhat al-Nusra, the jihadist group that shares the worldview of the late al-Qa’ida leader, Osama bin Laden, which has become increasingly prominent on some of the battlefronts of Syria’s civil war, inclusing Aleppo.

The confession was derided by every one of the 11 people interviewed by the Guardian as well as dozens of others that came and went from the Revolutionary Security centre during the week we were there. Jabhat al-Nusra members are visible on the streets of eastern Aleppo and play prominent roles in distributing food and aid to some communities.

They are distrusted by some rebel groups who vie with them for fighting honours and subsequent spoils of war. But they are feared by few on the rebel side.

“They’re not good guys,” said Amhed al-Sobhi, a hospital worker. “They don’t think like me, but they behave respectably. They do not kill civilians. You would have to be willfully blind to not know who did this massacre.”

“Jabhat al-Nusra won’t do such a horrible thing,” said Amer al-Ali. “No muslim can do such a thing but this regime can do it. You call us terrorists. come and fight us face to face.

Sheikh Aurora was emphatic: “Jabhat Al-Nusra is more honest and noble than Bashar and his gang. They would not commit such a crime. It was Jabhat al-Nusra who provided people with food, shelter and clothes. Why would they give them with all of these things and then kill them?”

The Guardian