What happens with thinkers who operate outside the European philosophical ‘pedigree’?

In a lovely little panegyric for the distinguished European philosopher Slavoj Zizek, published recently on Al Jazeera, we read:

There are many important and active philosophers today: Judith Butler in the United States, Simon Critchley in England, Victoria Camps in Spain, Jean-Luc Nancy in France, Chantal Mouffe in Belgium, Gianni Vattimo in Italy, Peter Sloterdijk in Germany and in Slovenia, Slavoj Zizek, not to mention others working in Brazil, Australia and China.

What immediately strikes the reader when seeing this opening paragraph is the unabashedly European character and disposition of the thing the author calls “philosophy today” – thus laying a claim on both the subject and time that is peculiar and in fact an exclusive property of Europe.

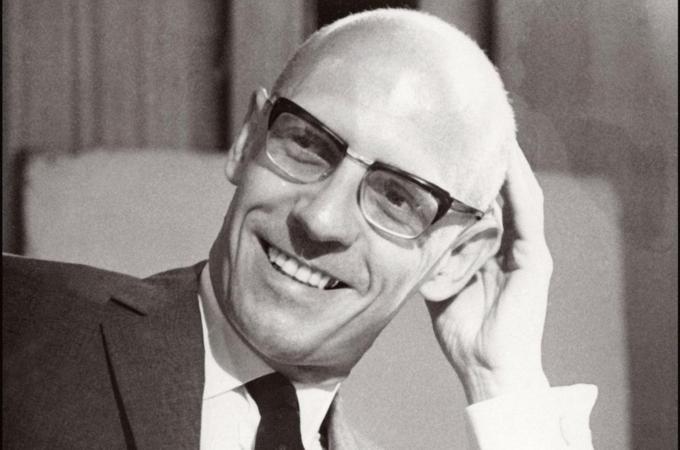

Even Judith Butler who is cited as an example from the United States is decidedly a product of European philosophical genealogy, thinking somewhere between Derrida and Foucault, brought to bear on our understanding of gender and sexuality.

To be sure, China and Brazil (and Australia, which is also a European extension) are cited as the location of other philosophers worthy of the designation, but none of them evidently merits a specific name to be sitting next to these eminent European philosophers.

The question of course is not the globality of philosophical visions that all these prominent European (and by extension certain American) philosophers indeed share and from which people from the deepest corners of Africa to the remotest villages of India, China, Latin America, and the Arab and Muslim world (“deep and far”, that is, from a fictive European centre) can indeed learn and better understand their lives.

That goes without saying, for without that confidence and self-consciousness these philosophers and the philosophical traditions they represent can scarce lay any universal claim on our epistemic credulities, nor would they be able to put pen to paper or finger to keyboard and write a sentence.

Thinkers outside Europe

These are indeed not only eminent philosophers, but the philosophy they practice has the globality of certain degrees of self-conscious confidence without which no thinking can presume universality.

The question is rather something else: What about other thinkers who operate outside this European philosophical pedigree, whether they practice their thinking in the European languages they have colonially inherited or else in their own mother tongues – in Asia, in Africa, in Latin America, thinkers that have actually earned the dignity of a name, and perhaps even the pedigree of a “public intellectual” not too dissimilar to Hannah Arendt, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Michel Foucault that in this piece on Al Jazeera are offered as predecessors of Zizek?

Are they “South Asian thinkers” or “thinkers”, the way these European thinkers are? Why is it that if Mozart sneezes it is “music” (and I am quite sure the great genius even sneezed melodiously) but the most sophisticated Indian music ragas are the subject of “ethnomusicology”?Do the constellation of thinkers from South Asia, exemplified by leading figures like Ashis Nandy, Partha Chatterjee, Gayatri Spivak, Ranajit Guha, Sudipta Kaviraj, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Homi Bhabha, or Akeel Bilgrami, come together to form a nucleus of thinking that is conscious of itself? Would that constellation perhaps merit the word “thinking” in a manner that would qualify one of them – as a South Asian – to the term “philosopher” or “public intellectuals”?What about thinkers outside the purview of these European philosophers; how are we to name and designate and honour and learn from them with the epithet of “public intellectual” in the age of globalised media?

Is that “ethnos” not also applicable to the philosophical thinking that Indian philosophers practice – so much so that their thinking is more the subject of Western European and North American anthropological fieldwork and investigation?

We can turn around and look at Africa. What about thinkers like Henry Odera Oruka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Okot p’Bitek, Taban Lo Liyong, Achille Mbembe, Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, Souleymane Bachir Diagne, V.Y. Mudimbe: Would they qualify for the term “philosopher” or “public intellectuals” perhaps, or is that also “ethnophilosophy”?

Why is European philosophy “philosophy”, but African philosophy ethnophilosophy, the way Indian music is ethnomusic – an ethnographic logic that is based on the very same reasoning that if you were to go to the New York Museum of Natural History (popularised in Shawn Levy’s Night at the Museum [2006]), you only see animals and non-white peoples and their cultures featured inside glass cages, but no cage is in sight for white people and their cultures – they just get to stroll through the isles and enjoy the power and ability of looking at taxidermic Yaks, cave dwellers, elephants, Eskimos, buffalo, Native Americans, etc, all in a single winding row.

The same ethnographic gaze is evident in the encounter with the intellectual disposition of the Arab or Muslim world: Azmi Bishara, Sadeq Jalal Al-Azm, Fawwaz Traboulsi, Abdallah Laroui, Michel Kilo, Abdolkarim Soroush. The list of prominent thinkers and is endless.

In Japan, Kojan Karatani, in Cuba, Roberto Fernandez Retamar, or even in the United States people like Cornel West, whose thinking is not entirely in the European continental tradition – what about them? Where do they fit in? Can they think – is what they do also thinking, philosophical, pertinent, perhaps, or is that also suitable for ethnographic examinations?

The question of Eurocentricism is now entirely blase. Of course Europeans are Eurocentric and see the world from their vantage point, and why should they not? They are the inheritors of multiple (now defunct) empires and they still carry within them the phantom hubris of those empires and they think their particular philosophy is “philosophy” and their particular thinking is “thinking”, and everything else is – as the great European philosopher Immanuel Levinas was wont of saying – “dancing”.

The question is rather the manner in which non-European thinking can reach self-consciousness and evident universality, not at the cost of whatever European philosophers may think of themselves for the world at large, but for the purpose of offering alternative (complementary or contradictory) visions of reality more rooted in the lived experiences of people in Africa, in Asia, in Latin America – counties and climes once under the spell of the thing that calls itself “the West” but happily no more.

The trajectory of contemporary thinking around the globe is not spontaneously conditioned in our own immediate time and disparate locations, but has a much deeper and wider spectrum that goes back to earlier generations of thinkers ranging from José Marti to Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, to Aime Cesaire, W.E.B. DuBois, Liang Qichao, Frantz Fanon, Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, etc.

So the question remains why not the dignity of “philosophy” and whence the anthropological curiosity of “ethnophilosophy”?

Let’s seek the answer from Europe itself – but from the subaltern of Europe.

‘The Intellectuals as a Cosmopolitan Stratum’

In his Prison Notebooks, Antonio Gramsci has a short discussion about Kant’s famous phrase in Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) that is quite critical in our understanding of what it takes for a philosopher to become universally self-conscious, to think of himself as the measure and yardstick of globality. Gramsci’s stipulation is critical here – and here is how he begins:

Kant’s maxim “act in such a way that your conduct can become a norm for all men in similar conditions” is less simple and obvious than it appears at first sight. What is meant by ‘similar conditions’?

To be sure, and as Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith (the editors and translators of the English translation of Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks) note, Gramsci here in fact misquotes Kant, and that “similar conditions” does not appear in the original text, where the German philosopher says: “I am never to act otherwise than so that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law.” This principle, called “the categorical imperative”, is in fact the very foundation of Kantian ethics.

So where Kant says “universal law”, Gramsci says, “a norm for all men”, and then he adds an additional “similar conditions”, which is not in the German original.

What in effect Gramsci discovers, as a southern Italian suffering in the dungeons of European fascism, is what in Brooklyn we call chutzpah, to think yourself the centre of universe, a self-assuredness that gives the philosopher that certain panache and authority to think in absolutists and grand narrative terms.That misquoting is quite critical here. Gramsci’s conclusion is that the reason Kant can say what he says and offer his own behaviour as measure of universal ethics is that “Kant’s maxim presupposes a single culture, a single religion, a ‘world-wide’ conformism… Kant’s maxim is connected with his time, with the cosmopolitan enlightenment and the critical conception of the author. In brief, it is linked to the philosophy of the intellectuals as a cosmopolitan stratum”.

Therefore the agent is the bearer of the “similar conditions” and indeed their creator. That is, he “must” act according to a “model” which he would like to see diffused among all mankind, according to a type of civilisation for whose coming he is working-or for whose preservation he is “resisting” the forces that threaten its disintegration.

It is precisely that self-confidence, that self-consciousness, that audacity to think yourself the agent of history that enables a thinker to think his particular thinking is “Thinking” in universal terms, and his philosophy “Philosophy” and his city square “The Public Space”, and thus he a globally recognised Public Intellectual.

There is thus a direct and unmitigated structural link between an empire, or an imperial frame of reference, and the presumed universality of a thinker thinking in the bosoms of that empire.

As all other people, Europeans are perfectly entitled to their own self-centrism.

The imperial hubris that once enabled that Eurocentricism and still produces the infomercials of the sort we read in Al Jazeera for Zizek are the phantom memories of the time that “the West” had assured confidence and a sense of its own universalism and globality, or as Gramsci put it, “to a type of civilisation for whose coming he is working”.

But that globality is no more – people from every clime and continent are up and about claiming their own cosmopolitan worldliness and with it their innate ability to think beyond the confinements of that Eurocentricism, which to be sure is still entitled to its phantom pleasures of thinking itself the centre of the universe. The Gramscian superimposed “similar conditions” are now emerging in multiple cites of the liberated humanity.

The world at large, and the Arab and Muslim world in particular, is going through world historic changes – these changes have produced thinkers, poets, artists, and public intellectuals at the centre of their moral and politcial imagination – all thinking and acting in terms at once domestic to their immediate geography and yet global in its consequences.

Compared to those liberating tsunamis now turning the world upside down, cliche-ridden assumption about Europe and its increasingly provincialised philosophical pedigree is a tempest in the cup. Reduced to its own fair share of the humanity at large, and like all other continents and climes, Europe has much to teach the world, but now on a far more leveled and democratic playing field, where its philosophy is European philosophy not “Philosophy”, its music European music not “Music”, and no infomercial would be necessary to sell its public intellectuals as “Public Intellectuals”.

Hamid Dabashi is the Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. Among his most recent books is The World of Persian Literary Humanism (2012).

Al Jazeera